In the year and change since Joan Didion passed away in December 2021, a feeling has regularly come over me that I can only describe as animosity. I noticed it when I taped a podcast with Bret Easton Ellis. Ellis is a well-known Didion fan and a casual expert on her life and milieu. As I drove home from taping, a friend called, who knew I had been nervous, and asked me how it went. As often happens post-interview, I had a terrible vulnerability hangover. I told her, “I heard myself say to him, ‘I feel like Joan Didion didn’t eat so you know she didn’t fuck.’” My friend was quiet for a moment, and then said generously, “I’m sure it had a context.”

Then last September, I was at the Sunset Tower with Lili Anolik, a writer, and Karah Preiss, a producer and founder of Belletrist, having coffee. We were discussing Lili’s piece in Vanity Fair about Eve Babitz’s letters to Joan Didion. It’s no secret that Lili has sided with Eve in this hypothetical feud. She believes that Eve was the genius, but Joan was the winner. We discussed the forthcoming auction of Joan Didion’s things—her Le Creusets, embroidered table linens, blank notebooks. The auction website had already crashed due to traffic. It was going to be a shitshow. Lili half-laughed and looked at me: “Can you imagine saying that Joan Didion was your favorite writer?”

I half-laughed. That, too, had a context.

When I was sixteen, I was sent away from sunny, stoned, surf-heavy Seal Beach, California, to live with my father in farm country outside Boulder, Colorado. I’ve written about this move and its fallout a few times (you can read a relevant excerpt from my memoir here), but suffice to say, the situation was difficult. I started a private school that was half prep school and half daycare for troubled kids. For two months, I did not make a friend.

Every lunch period, I sat in the phone booth in the school’s basement with an AT&T long-distance card and called my boyfriend in California. He was older, in community college, and we had been wrung apart against our will. After we plotted (I was going to get emancipated from my parents, I was going get myself admitted to a mental hospital to get away from my parents, we were going to get married immediately upon my eighteenth birthday) and I hung up, I would read. The Moviegoer by Walker Percy. Murakami and Camus. All of Toni Morrison. Then I read Play It As It Lays.

For the first time, I realized the place I had been banished from wasn’t just “California,” where girls in high school got breast implants for their sixteenth birthday, and the highest achievement was gaining admission to USC. We were the product of a mythology spanning generations, and our values were born of those beliefs. We were all unthinkingly in its thrall. To understand that the place you were raised was shaping you more than you could ever shape it is one of the more universal facets of growing up. I would have gotten there eventually—but Didion kickstarted that knot of nostalgia and cynicism I call homesickness.

That fall, I also read The White Album, and then Slouching. I want to tell you that I look back on that period of adolescent angst fondly and with gentle contempt, that I call it immature. But I’m not sure I’ve grown much since then. The shadow of those months of reading still shade my life. We think of shadows obscuring, but mine, I’m realizing as I write, have been mostly generative.

*

When did my unadulterated admiration grow uneasy? Most likely it started the day she died. I saw a tweet that read, “oh the onslaught of personal essays we’re going to have to endure now that Joan Didion died.” Another: “please don’t write a personal essay about your personal relationship to Joan Didion.” And later, during said onslaught of personal essays—nearly all of them half-eulogy, half book report—I felt repelled. Wasn’t she suspicious of sentimentalizing stories? Wouldn’t she have hated that?

Then a writer called me to get a quote about the Joan Didion auction for an article. I was supposed to give a quippy line or two about her impact and legacy. I found myself talking at length, and not necessarily kindly. The frenzy for her objects, though for an extremely worthy cause, made me uncomfortable.

A friend texted, You bidding on JD’s aprons? I wrote back, Not my thing, while thinking to myself, Who the fuck would spend money on her aprons? Who would buy a stack of books by her “favorite” writers? What secrets did they expect to glean from the underlining and highlighting, from the margins of her life? I didn’t believe the person buying those books was going to read Graham Greene or Norman Mailer. (If you want to get close to Didion, Joseph Conrad’s Victory was the novel she reread before she started each of her own novels.) I realized that I didn’t think the person who bid at the auction was even going to really read Joan Didion.

Getting closer to my irritation, I don’t like that Joan Didion has become a meme. A tote bag. Celine sunglasses. A column dress and a Stingray. Wire baskets hanging in the kitchen. A “cult.” Of course everyone reveres Joan Didion. She’s peerless. It’s troubling to me that her real legacy - in our increasingly visual age - seems to have be the way she looks. She - not her words, but more her face - has become a commodity, traded, used to signal what kind of woman/reader/writer/Californian you are. And I was as guilty of it as anyone else.

*

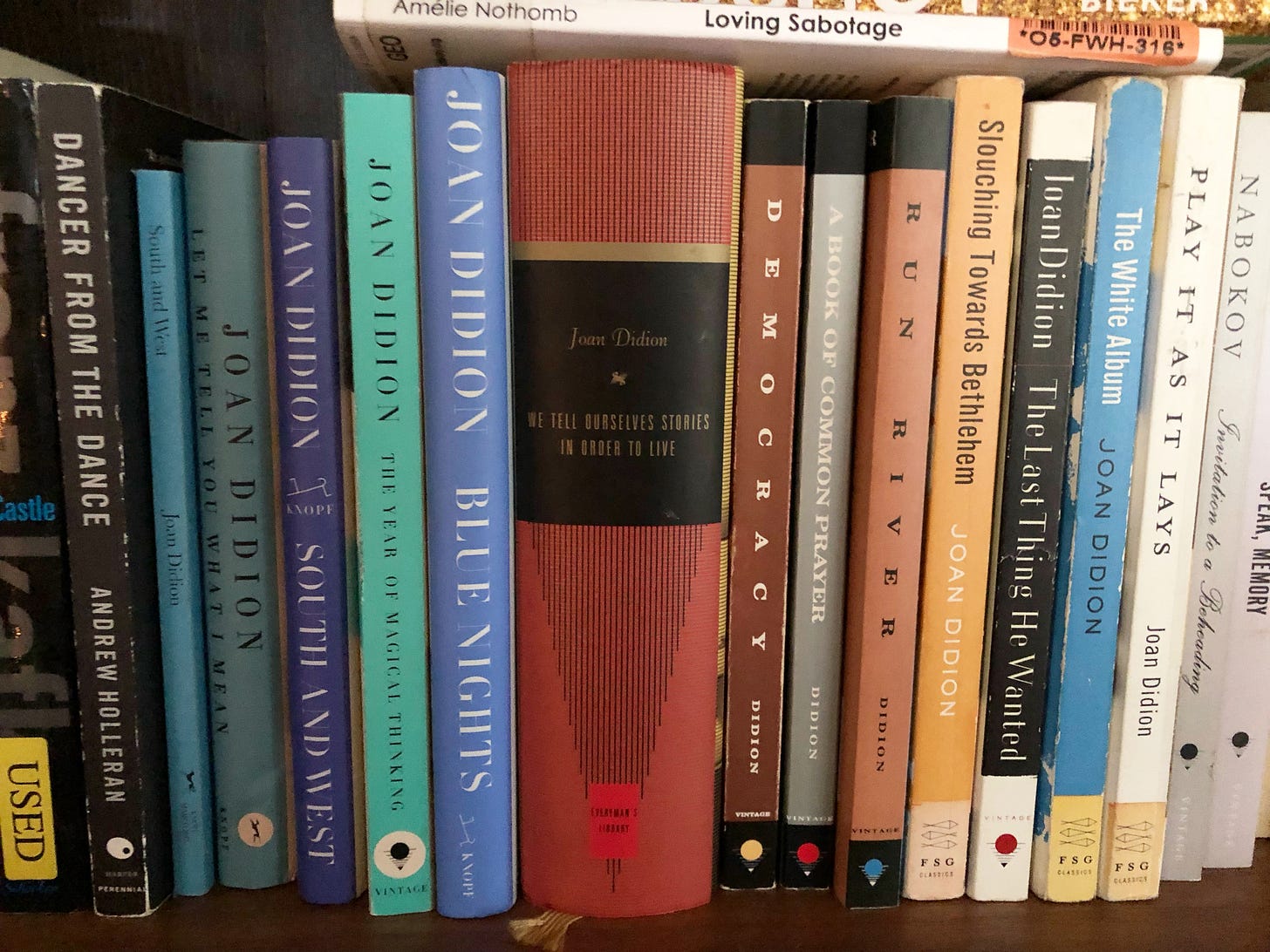

My aversion to those essays responding to Didion’s passing was my own poorly made-over shame. I think my friend Lili knows this and knew it at the Sunset Tower: Joan Didion is my favorite writer. Isn’t she? Didn’t I slog through all of Miami? Didn’t I write a paper in college on how she invented the central metaphor for Los Angeles in “The Santa Anas?” Don’t I read her in some form before starting any writing project? Even this one?

*

I don’t write like Didion, though I have readers who assure me I do. It’s not a comparison I court. I see a lot of quotes on the back of books comparing said author to Joan Didion, and I think doing so is generally weak and reductive, a disservice to both. If one writes about California, is one Didion’s heir because that’s the only kind of writing about California there can possibly be? But she did teach me how to write, and she modeled what being a woman and writer could look like (I don’t mean physically—my copy of Play It As It Lays lacked an author photo).

Later, though, I did sometimes want to be the Didion of photographs. I wanted her controlled femininity and her Hemingwayesque arrogance, and I wondered how she as allowed to have both (my guess is it has something to do with her avoidance of overt sexuality. Show me a Didion character who has an orgasm or has any carnal knowledge). I wanted what Zadie Smith accurately identified in her Didion remembrance for the New Yorker: “the authority of tone.”

*

I reread Salvador a few months ago, and it was startlingly good. Not as a piece of war journalism, it’s too subjective, but a piece in which the lens of the traveler is the focus, the American-ness is what’s being observed (it’s of note that this inward gaze is what many do not like about this book). As always, she is her own subject.

Consider the opening of Salvador:

The three-year-old El Salvador International Airport is glassy and white and splendidly isolated, conceived during the waning of the Molina “National Transformation” as convenient less to the capitol . . . than to a central hallucination of the Molina and Romero regimes, the projected beach resorts, the Hyatt, the Pacific Paradise, tennis, golf, water-skiing, condos, Costa del Sol; the visionary invention of a tourist industry in yet another republic where the leading cause of death is gastrointestinal infection. In the general absence of tourists, these hotels have since been abandoned, ghost resorts on the empty Pacific Beaches, and to land at the airport built to service them is to plunge into a state in which no ground is solid, no depth of field reliable, no perception so definite that it might not dissolve into its reverse.

Here are the concerns of her entire oeuvre: delusional mythology, an obsession with surfaces, lies being bought then sold (“glassy,” “white,” “isolated,” gesturing toward an oasis but also a mirage, the “glassy” also a mirror, the “white” a gesture toward purity). Beautifully done, the idiocy of “water-skiing” up against the poverty. When Joan is being Joan, there is, truly, no one better. But it’s not just Salvador where no perception is definite—it’s all her work. She is always interrogating, therefore always adrift.

*

What am I saying when I criticize Saint Joan? I don’t think it’s just the contrarian in me, though that vein is deep, entrenched. I think I’m criticizing the way we use her without really reading her. To me, reading her means engaging with her flaws, her limits. For such an incisive writer, she had truncated breadth. That passage I love from Salvador is at home in any of her pieces, fiction or nonfiction, the ones from the late 60s or early 90s—it’s the Didion beat. She endlessly circles the center that will not hold.

*

Today it seems the best-case scenario invoking her is that one channels a certain kind of cool: the nipples showing through the white shirt, her feet in the ocean, or her chic variety of mental instability (the urban neurotic whose disorders are credible but don’t hinder their ability to make vichyssoise), what Hilton Als calls, her “white-woman fragility.”

Then there are more fraught realizations. Isn’t the woman who says Joan Didion is her favorite writer telling you that she’s a winner? And not by luck or happenstance but by birth and will and extremely careful manipulation of her image. I think of Joan’s awareness that writing is a hostile act, and that as “the writer,” she is the victor who writes history. Her self-fashioning is scarily cunning. It isn’t just her packing list, her career at Vogue, her finish-each-other’s-sentences marriage. Her reliance on details of provenance, on night-blooming flowers. Every single word Didion has written about herself is aspirational lifestyle porn.

*

From that lifestyle, I gleaned something invaluable: a blueprint for a career constructed from words. For Didion, writing is not a vocation practiced in a monastery. It is not a gift or sacrifice offered on the altar. Or at least it’s not only those things. It’s a job, with the worry about when and where is the next one, and the one after that. Not just a blueprint, though. I also ended up a writer who fears I rely too much on style, fears I signal too much and the wrong things. It’s clear what bothers me about Didion are things I fear for myself.

*

When I say favorite, it means the most instructive, the most reread, the most totemic. Often these are writers you find in the unpleasant miasma of becoming, writers who urge you toward mimicry, but then, finally, hopefully, into your own voice. Their words are your intimate, maybe in some cases your parent, alerting you to the dangers ahead. Only just now is it clear that I have grown critical of Didion because I left that phone booth outside Boulder, Colorado. I grew up. She is the godlike parent turned mortal, an idol I had to dismantle to become a writer. I can’t imagine a frame of reference for what I do without her, but mostly these days, when I see her mentioned, I’m—dare I say it—bored.

This past November, a friend and I went to “Joan Didion: What She Means” at the Hammer Museum. It was a temperate day and luxurious to be away from our desks. We took pictures of each other in front of Brigette Lacombe’s wall-sized photo of Didion hiding her face inside a turtleneck. This is a photo of her I love. I relate to wanting to disappear my face, my brain, my persona. I didn’t know what to expect from the show—mementos, memorabilia, first editions? An immersive experience of that auction? Instead, Hilton Als curated a response to her writing with the art of others. Upon entering, it felt random: What was I looking at? Why were there gold-leafed bricks stacked on the floor (Amanda Williams’s It’s a Goldmine/Is the Gold Mine?)? And I do love Every Building on the Sunset Strip, but Ed Ruscha, yet again? Then I submitted to the exhibit. I felt the associative echoes between Didion’s obsession with water in the west and the steel chains and rope in Maren Hassinger’s River. I gasped when I saw Ana Mendieta’s Untitled: Silueta Series, in which the artist took photographs of the imprint of a woman’s body left in the sand, and the imprint eventually washes away. Combined, they’re a portrait of an erasure. I heard another person inside refer to the show as “weird,” and that’s correct. It was a weird (singular, peculiar, slightly ominous) mosaic of Didion “written” by another artist. Let it be difficult, I thought, let her be thorny. I was not bored. We sat on a bench outside, and my friend asked what I thought.

“I loved it,” I said. “It had so little to do with Joan Didion.”

Thank you for reading (“thank you” feels woefully inadequate to express how I feel about this silly and impossible newsletter existing).

In two weeks, I’ll send out recommendations. just after that, I’ll send out the first video . Until then, I’ll be in the comments. Please say hello.

Curious about a book mentioned above? They’re all available at my author bookshelf.

She’s definitely one of my favorite writers but I’m more into her non-fiction than her fiction (although Play It... I do love). I’m a fan of Hemingway too; I think it was the Brontes and then Hemingway that were the first writers I really admired. I came late to Didion despite having grown up for a short, formative time in LA. And I’m no stranger to criticism of her work; for every friend I have who loves her there is another who hates how precious she is, or a professor who told me that Didion is a hypocrite because she left so much truth and reality out of her so-called personal essays. I just don’t care, frankly. I love her writing. I wish I had mastery of a tone like that. She’s instructive. But whenever a “cult” forms around somebody... it’s like you said, it renders the person or thing quite boring. (I also really like Babitz’s writing, although it’s so much less affected and precise; maybe I like it for exactly those reasons.)

aspirational lifestyle porn … a life long New Yorker but after reading Magical Thinking I thought maybe I need to live in Brentwood? I was a new wife in my mid twenties … Vanessa Redgrave was finishing her run on Broadway and I started doing this thing where I read books that made me sob on airplanes. I still do it. It was the tone I fell in love with. But also why are we so obsessed with out street cred? Of being above the fray? Why do we have to justify that our favorite is irreproachable? I love the books and the movies and the Celine ads and the way I sobbed on a transcontinental from NY to San Fran.

Also, I loved Sweetbitter because it took me back to being twenty and lost in my self and more in love with New York than anyone or anything. That makes you a favorite. I hope that doesn’t make me boring :)