A Class Story

We all have one.

Two months ago, I was having a drink with my friend Emily Tomson, a writer and director. We were talking about raising our children in the sprawling kingdom of Los Angeles, and I told her that I had been rattled recently when I took Julian on a playdate at a classmate’s house in Los Feliz. The house, on a one-acre lot, had a two-story guest house and a pool. There was a play structure adjacent to a small soccer field on the manicured lawn. The skylit toy room was the size of my living and dining room combined, and it included a ball pit. There were staff hovering just out of sight (nanny, interior decorator), and the implication of additional staff in the hyper-organized, spotless shelves of the refrigerator, the prepped meals labeled with dates. There was a lack of concern about spills or messes or wasted food. Neither parent had what I would call “a job.” This level of wealth is something I’ve gradually become accustomed to, and it’s not especially shocking by Los Angeles standards. I’ve been to more extravagant houses both as an employed server and as a guest. But I was upset, not at the house exactly, but because my son asked me, as we were leaving, “When can we live in a house like X’s?” He did not want to go home. It was the first time I’ve seen him experience real, anxious envy. My breath hitched in my throat. “Never,” I said. I cried (subtly and quietly, disgusted with myself) on the drive home.

*

In nearly every review of my memoir Stray—even the positive ones—there was mention of my privilege. That didn’t surprise me. I remember reading a piece in N+1 back in 2014 about the way privilege had become the primary lens for literary criticism, and that particular form of scrutiny has only increased in the years since. But I was also aware from everyday social interactions that my life didn’t appear to warrant a memoir. I struggled for years thinking my story did not contain enough pain, deprivation, or event. I didn’t survive a natural disaster, or even weather a capitol-T trauma. There was no car crash, no illness diagnosis, no literal fight for life. Yet I knew from publishing short pieces that I had something to say about neglect and abuse, an experience that was much more universal than I ever imagined as a child. I also knew that my life was irredeemably charmed. But I was surprised that reviewers and some readers wanted clarity on my class and general socioeconomic standing, which I believed was embedded in every single detail. What, in telling my own story, had I left out?

There was a point during the writing of Stray when I considered writing about money: how its presence and lack shaped me and my ambitions in not so obvious ways, how I went from defiantly not caring about it to feeling like it is the only thing that will protect my family. But money felt so disruptive—the issue is fucking enormous, all of its scars made up of a thousand tiny cuts. And Stray, whatever else it is, is small. It’s the prism of a single moment through which I see my past and potential future: my parents’ addiction and abandonment, my awful love affair, my own alcohol and drug abuse. I never intended to write, nor did I know how to write, about all of it. I didn’t write about my years in the restaurant industry or my years as a wine buyer. I elided most of college and my first marriage. I didn’t write about the selling of Sweetbitter or my sexual coming of age. Stray was not—couldn’t be—about those things. And while I did not write overtly about money and privilege, it is undoubtedly at the center of what shaped Stray, because it is, just barely above sex, the idea that has most obsessed me.

*

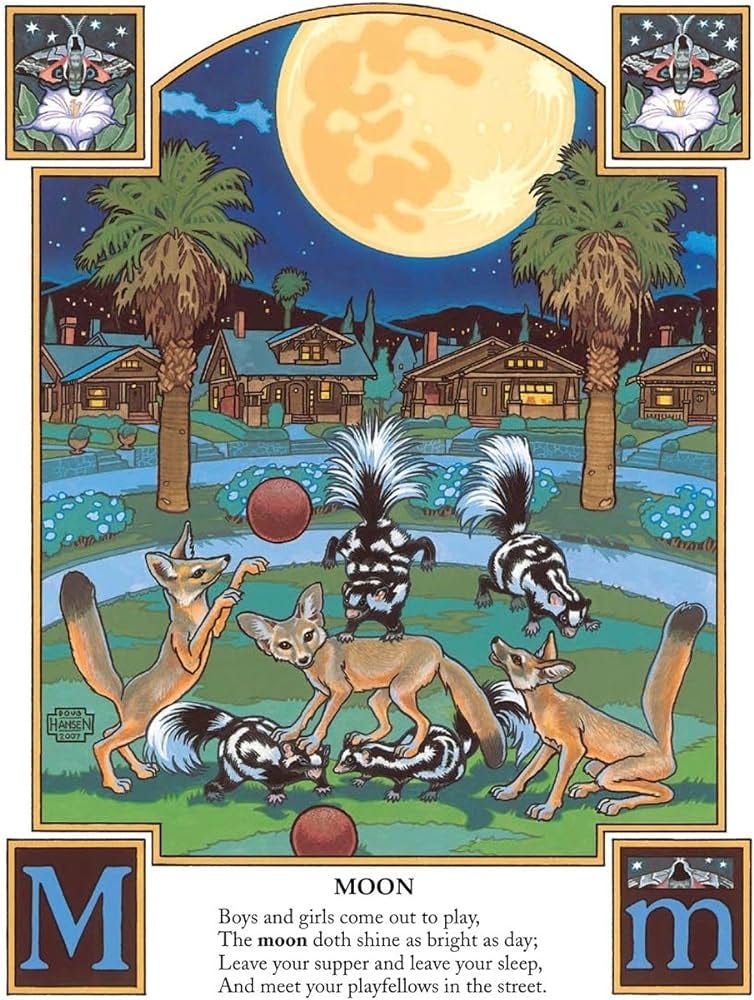

I am almost physically attracted to old houses, with their quirks and inconveniences. Ours is a Craftsman built in 1906, and it’s full of turn-of-the-century weirdness. The one bathroom is tiny, storage-less, and the shower rigged in the cast iron tub feels makeshift. The kitchen is also weirdly cramped, and the ancient Chambers stove needs repairs at least quarterly. We have no closet in our bedroom and share with our children. Matt and I often talk about what the city must have looked like when the house was built. In 1907 they started construction on the Silverlake Reservoir, hoping to create an emergency water supply (a dream that died on the vine as the growing city quickly outstripped its natural resources). The house was probably surrounded by farmland (maybe lima-bean fields or citrus groves or vineyards). Nearby, the Los Angeles River would have had riverbanks covered in willows and sycamores, as opposed to its current concrete. The city had an extensive trolley network at that time, and one ran next to the house on a single lane of packed dirt that was eventually paved and named Sunset Boulevard.

When we got home from the playdate in Los Feliz, I reminded my kids about our house’s specialness: its stained-glass window panes, its ornate built-in bookshelves, our large front porch, all of which the owner, Julie, had lovingly restored. She had lived in it in the early nineties, renting it from an owner who left it trashed, rat-infested, with holes in the walls that the winds whistled through. I point out to my kids the way afternoon light grazes the nicks in the dark wood staircase, the way the house stays cool on hundred-degree days. We are constantly harping on the idea of being good stewards of Julie’s magical house. We are lucky to be able to live in Silverlake, holding onto our stabilized rent while our friends all push east. When we drive up after time away, we look at each other and say, “Can you believe we live here?”

Who had I become that I would cry over a wealthy person’s house? When I said all of this to Emily, she talked about an exercise she had done in a social justice workshop. On the first day, the participants had gone around in what the workshop called a “story circle,” and each person told their class story. The intention was to center the personal story within the conversation they were about to have about identity politics. She had expected to talk about racism, activism, and socioeconomic issues, but not necessarily herself: “I had a fairly normal childhood, and I’m so privileged,” she started. And while she might have assumed her story was straightforward, upon telling it revealed itself to be complicated. She said to me, “ I was rocked by telling that story. I couldn’t stop crying. I realized for the first time how much this was a part of my identity. The shifts I went through as a child impacted the way I see everything.”

*

A class story. We all have one. And I suspect many of us are not in touch with the ways we were hurt by it, or by our ambivalence—even at times our defensiveness—of the privilege that counterbalances our hardship. How aware are we of how our class story still informs our aspirations and decisions? How are we unconsciously projecting it onto our loved ones?

I kept coming back to the phrase: class story. I toyed with writing one for myself. I haven’t done it yet (though this might be one of many first fitful starts). But what I did do was write one for the main character of my novel-in-progress.

I would argue that there is not an observation a fictional character can make that isn’t informed by the material reality of how they grew up, and how they in turn present a coherent identity to others, how they choose everything from their hairstyle to their politics. If I’m honest with myself, my values are grossly entwined with what my parents wanted and what I couldn’t have. It makes sense then that the same is true for the main character of my novel.

If we can imagine more fully the class story of our characters, we can better inhabit their point of view. We can better load up the details they’re tracking, intuit their responses, project their hopes, and move from their conscious motivations to the unconscious. For my novel in progress, my protagonist (let’s call him H) returns to Los Angeles anxiously. I thought he was anxious because of a tragedy in his past—though that’s certainly part of it—but he’s primarily anxious about his proximity to a certain class of people and circumstances that we now call the 1 percent. How his milieu intersects with his personal tragedies is one of the main threads of the novel. Can intimate, trusting friendships develop across class lines? Can marriages that cross those lines be equitable, or is someone always the guest, the help? Do we unfailingly experience schadenfreude at the humiliations and undoing of the elite? Does H want power because he has suffered or because he finds its execution alluring?

I don’t want to oversell the exercise—it wasn’t a critical breakthrough for my book. But I understood so much more clearly what H notices (and the first-person voice is entirely constructed by what the character notices) especially as it relates to what he wants. Character development is understanding what undergirds those wants. For that kind of discovery, this exercise is hugely helpful. I mean, hugely. When writing, we are often talking about stakes. We do so because stakes turn a want into a need. A character can want money—but what specifically will turn that want into a need?

Emily shared some prompts from her workshop (I’ve shared them below). They felt revelatory and uncannily familiar, like something dredged up from a dream. I shivered when I read, “Have you ever been able to take an unpaid internship?” The summer after my sophomore year in college, I moved to New York City along with a small group of friends, some of whom took unpaid internships: at Random House and the New York Times. In the celebrity-frequented office of a naturopath doctor downtown. At 42West and the Second Stage. And five mornings each week, and occasionally overnight, I wore an industrial back brace and unloaded pallets in the bowel of Borders Books in the Time Warner Center. (I had a friend there, Samara, and we ran a racket where we tore the covers off the expired pornographic magazines and pretended to return them, but we actually traded them to the cooks and dishwashers at Per Se. She asked me once, “Why the fuck do you want to move to here?” I said, sarcastically, “Because I love Sex and the City.” When she laughed at me, I wondered if I was joking.) At the time I would have told you I didn’t care—about my job or Samara’s laughter or my friends’ good fortune. My friends (mostly their parents) were generous: I got to see Broadway plays, raided stocked fridges in their townhouses, spent weekends at second homes in the Hudson Valley, Vermont, Fire Island. I enjoyed a veritable buffet of hand-me-downs. I was impervious to being different from my peers. Yet now, as an adult, the words unpaid internship make me involuntarily grimace. It’s clear to me now that I was so, so ashamed.

*

As I thought about these class-story questions, I felt like scenes, even entire short stories, could fall into my lap with each answer. But the exercise also made me imagine the class story my children will be telling someday. Dear God, it can’t be that I cried in the driveways of rich people’s houses! But those thousand tiny cuts I mentioned do linger: maybe if I hadn’t had to work thirty hours a week in high school, I wouldn’t have failed so many classes. Maybe all those times a friend covered me because we had gone to the ATM and my balance was near zero had left me with the impression that I am always both in debt and undeserving. Maybe if my mother hadn’t been so focused on our perpetual lack and berated herself for it, I wouldn’t cry over a child’s toy collection. When my son asked me that question, it took me back to being small, scared, and confused as to why other people’s homes seemed lighter than mine.

What is surprising about your own class story? Perhaps you straddled two classes, or moved up or down in ways that felt inexplicable to your younger self. Or you had one class experience with one parent and a different one with another. Perhaps you didn’t grow up in a two-parent household (I didn’t), and that was part of your story. Did your parents own their home? Did they graduate from college? Or maybe your parents held upper-middle class jobs that gradually stopped providing a corresponding lifestyle (I’m thinking of what Barbara Ehrenreich called the “professional-managerial class” like academics and social workers, nurses and middle managers who, as she explains, are “salaried mental workers who do not own the means of production”).

Do you know what was especially surprising about asking my main character to tell his class story? I had judged him. His proximity to wealth, ease, and vanity had allowed me to ignore what should have been obvious tensions. He appears, especially when we meet him, charmed. Though I know he has suffered (I made him to suffer), I didn’t realize how much my character hates the citizens of Beverly Hills (where the novel is set). Hates that they didn’t earn their money. Hates the bizarre and flimsy excuses they use to justify cruelty. He hates that they are not subject to the same rules as others. He hates that his own worth is inextricably tied to theirs—they gave him his power and can take it away. He would give anything to be them.

Don’t ask me how I know.

*

I don’t hate the couple who own that house in Los Feliz. But I don’t know why some people are born into shapes and spaces designed to inoculate them from discomfort, let alone hardship. I say I don’t know how I became a member of the creative class, but it has something to do with being born into a place where, despite financial precarity, it was even possible to conceive of being an artist. An artist—how outrageous is that? It feels random, careless, and confusing to navigate. And still, I can’t assuage that feeling of material envy for the cosseting and armoring that luxury objects perform .

As I can see my college-aged shame so clearly, I see I shouldn’t have hidden my tears from my children. I should have said, It’s ok to feel envy. It’s not a sin or a sign of greed. It’s just human. And it will pass. In the months since, I’ve remembered the episode and laughed. I’ve wondered what made me so sensitive, is it having children, or maybe the book I’m writing is dominating me in unexpected ways. And though I feel restored to my senses, it will happen again. I will wonder why I feel like I can’t make “enough” money, and I will be angry at myself when my children eventually compare themselves to other children and find what they have and who they are lacking. It hurts me. That’s part of my class story. If I hadn’t spent so long trying to bury or conquer my envy, I might have seen sooner that this is an old hurt. I’m not seven, or twenty, or twenty-nine. I’m nearly forty, and if I won the lottery—which in many, many ways I have—things would look mostly the same. Maybe I would get another master’s degree, or another five. I would probably make an offer on Julie’s house.

And while an aggressive pride in my “class story” was a defense mechanism against the affluence around me, that pride wasn’t totally misplaced. I smile when someone compliments me on my slightly deranged work ethic. The smile is not about endurance or hours logged at a desk. I smile because I really believe I can find a job anywhere, even if I find myself unloading pallets again. It’s those jobs I sometimes resented, not my education or my books, that gave me a resilient core. Would I really want to deny my children the same experience? Amid all the gross uncertainty of living, how fortunate would they be to have the rock-solid knowledge that they can take care of themselves?

Like all homes, ours is an expression of values. Dust. Piles of tiny dirty clothes in each corner. Mismatched table settings. The furniture is all secondhand. Books swallow up rooms. Organization is loose at best. The art that hangs is made by friends. We spend our time and money elsewhere: traveling when we can, simply existing in California. We have friends to visit in Los Osos, Joshua Tree, Santa Barbara, Santa Ynez, Santa Cruz, San Francisco, and Sea Ranch. No one will say we didn’t take advantage of this stupidly expensive and beautiful place. We spend too much on produce, eggs, and bread at the farmer’s market. We spend a lot on therapy. I can’t see these things when I look at my life, the way one sees art, watches, purses, or cars. They are invisible markers of a wealth I wasn’t raised to value. But as I mentioned before, I’m no longer being raised. I’m not a child (mostly not a child). This is where I get another chance. On the far side of these hang ups and obstacles, there has been—for me, when I can get there—an evergreen pasture of gratitude. I expect my children to meet me there.

Here are some class story prompts, based on those from Emily’s workshop:

Where did your family’s income come from? Investments? Public assistance? Salaries? Hourly wages?

What did the adults in your social circle do for a living?

What was your first job? Why did you get it?

Have you ever taken a break from paid work? Or taken an unpaid internship?

Think about the neighborhood and home you grew up in: Did most people own their homes and property? Were there public spaces in the neighborhood? Green spaces? A sense of community? Was it suburban or urban or rural? Who lived around you?

What did your leisure time look like? Did your family travel? Eat in restaurants? Did you go to summer camp? What were your sources of entertainment? Or hobbies?

Who cared for you when you were a child?

Did you have health care?

Did a family separation (death, divorce, imprisonment) impact your access to resources?

Compared to your parents or grandparents, what was your education like?

Was your family in debt? What were the sources?

Did your family have inherited wealth? Do you? What made that wealth possible?

What other identities (race, gender, dis/ability, sexual orientation) impacted your experience of class?

What do you appreciate about your class experience? And likewise, what has been hard?

While I’ve been at work on this essay something was in the ether: the podcast Classy by Jonathan Menjivar dropped. I devoured it, highly recommend. You can follow it up with Anne Helen Peterson’s interview with Jonathan on her substack, Culture Study.

Stephanie- I’ll reread several times. It strikes so many chords - my parents chaotic financial lives: so much and then nothing repeatedly ; my then undervaluing money; going to UCLA and working at the Beverly Hills Toy store in Beverly Drive- seeing Sheldon give gifts to the stars and their children and following black kids around the store; my own opportunity at immense wealth and my ex inability to keep a job while I never ever stopped working from the time I was 14. And maintaining authentic relationships with my wealthy friends while I was divorced and raising two boys in my own with no financial or practical help- still committed to giving them opportunities -and freaking out at night worried about money - it felt like my skin was on fire.

And that’s just the highlights ...

This reminds me of a comment a random screenwriter I met in Fort Greene park made after I told him the premise of my book--“who’s going to care about two white girls in Malibu?” I don’t know how to answer that question but I think this exercise in class can help me understand my characters more either way, and then perhaps answer his question for myself.